Irish Potato Farming: History, Culture, and Rural Life

Irish potato farming shaped more than diets. It shaped landscapes, families, and a national mindset rooted in endurance and adaptation. When we talk about Ireland’s rural past, the potato sits quietly at the centre of the story.

Farmers did not simply grow potatoes. They built a way of life around them.

Arrival of the Potato in Ireland

The potato reached Ireland in the late 16th century. Its appeal lay in simplicity. It thrived in poor soils, resisted harsh weather, and produced high yields from small plots. For tenant farmers, this mattered.

By the 18th century, potatoes sustained much of the rural population. Families depended on a single crop grown in ridged fields known as lazy beds. These beds improved drainage and warmth, allowing cultivation in marginal land.

This dependence carried risks, which history would later expose.

For deeper historical context, see The Influence of the Irish Potato Famine.

Farming Methods and Seasonal Rhythms

Irish potato farming followed strict seasonal rhythms. Farmers planted seed potatoes in spring and harvested them in late summer or early autumn. Families stored crops in clamps, simple underground pits that protected potatoes through winter.

Labour involved everyone. Children gathered stones. Adults cut seed potatoes by hand. Knowledge passed orally, much like Irish storytelling traditions still discussed in Why Are Irish People Natural Storytellers?.

These practices tied agriculture to culture. Farming became memory, habit, and inherited wisdom.

The Potato Famine and Its Lasting Impact

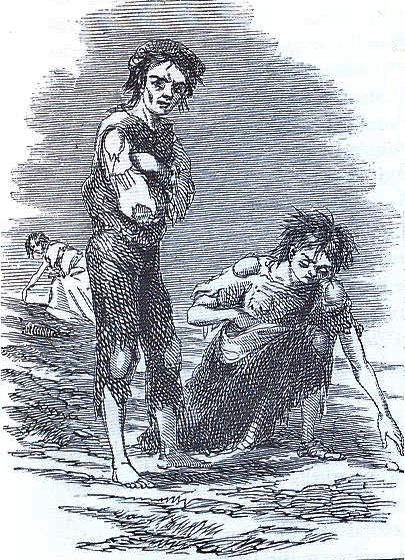

The Great Famine (1845–1852) marked a profound rupture. Blight destroyed crops repeatedly. Dependence on one variety left little resilience. Hunger, disease, and forced emigration followed.

Yet Irish farming did not disappear. It adapted.

After the famine, farmers diversified crops, improved drainage, and shifted toward mixed agriculture. Potatoes remained important, but never again stood alone.

The famine still echoes through Irish literature, music, and commemorative traditions, much like the symbolic weight carried by sites such as the Hill of Tara.

Potatoes in Modern Irish Agriculture

Today, Irish potato farming blends tradition with innovation. Farmers use disease-resistant varieties, crop rotation, and modern storage systems. Ireland exports high-quality potatoes across Europe.

Yet small-scale farming persists, especially in the west. In these regions, potatoes still anchor household gardens and local markets. Farming remains personal.

This continuity mirrors other living traditions, from Ceili Bands to rural crafts and seasonal festivals.

Cultural Meaning Beyond the Field

The potato became a symbol of survival. It appears in folk songs, proverbs, and oral histories. It also shaped migration patterns that spread Irish culture globally.

Even clothing traditions evolved alongside rural life. Farming communities wore durable garments suited to labor and climate. These choices later influenced cultural dress, explored further in Do Irish Wear Kilts?.

Agriculture never exists in isolation. It touches language, dress, music, and belief.

Why Irish Potato Farming Still Matters

Irish potato farming tells a story of resilience rather than loss. It shows how communities adapt under pressure while preserving identity. The fields may look quiet, but they carry centuries of memory.

Understanding this farming tradition helps us understand Ireland itself. Not as a romantic past, but as a lived, working landscape shaped by choice, hardship, and persistence.

For related rural perspectives, explore A Crofter’s Journey Through Time, which offers a parallel view from Scotland’s agrarian heritage.