The Declaration of Arbroath: Scotland’s Defiant Voice of Freedom

Few documents in European history speak with the moral clarity and political confidence of the Declaration of Arbroath. Written in 1320, this letter asserted Scotland’s independence during a period of deep crisis. More than a medieval appeal to the Pope, it became a statement of national identity that still resonates today.

As a historian trained in Scotland’s intellectual traditions, I see the Declaration not as a relic, but as a living text. Its ideas about sovereignty, leadership, and collective will remain strikingly modern.

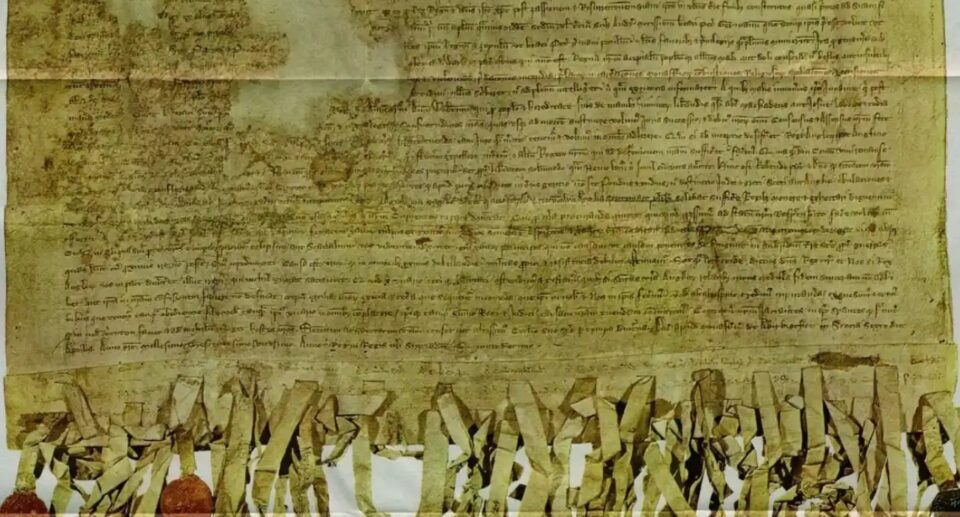

What Is the Declaration of Arbroath?

The Declaration of Arbroath is a formal letter sent to Pope John XXII in 1320. Scottish nobles and church leaders signed it at Arbroath Abbey. Their aim was clear. They wanted international recognition of Scotland’s independence from English rule.

The letter defended Robert the Bruce as Scotland’s rightful king. More importantly, it argued that political authority rests on the will of the people, not divine right alone.

👉 For broader Scottish historical context, explore the CeltGuide blog archive.

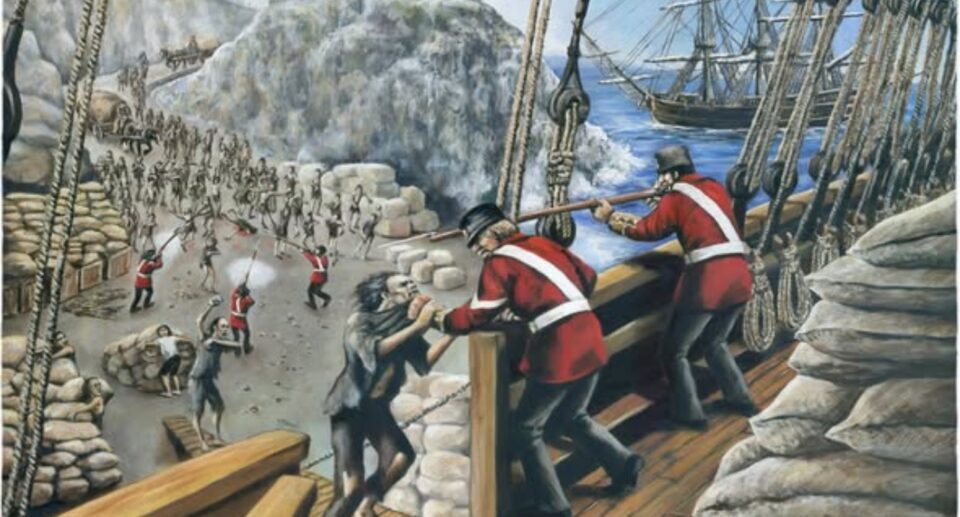

Why Was the Declaration Written?

By 1320, Scotland had endured decades of war with England. English kings claimed authority over Scotland, often through force. Scottish leaders needed diplomatic recognition to secure peace and legitimacy.

The Declaration framed Scotland as an ancient nation with its own laws, customs, and kings. This emphasis on continuity echoes the deep-rooted clan system explored in How Many Scottish Clans Are There?.

Rather than plead weakness, the authors asserted dignity. They spoke as equals on the European stage.

The Famous Passage That Changed Political Thought

One passage stands above the rest. It states that if the king fails to protect Scotland’s freedom, the people have the right to replace him. This idea predates later democratic theory by centuries.

That argument reshaped how sovereignty could be understood. Power flowed upward from the community, not downward from the throne.

This collective voice aligns with Scotland’s long tradition of oral and written expression, also seen in Irish narrative culture discussed in Why Are Irish People Natural Storytellers?.

Language, Faith, and Authority

The Declaration was written in Latin, the language of diplomacy and the Church. Its authors used biblical references and legal reasoning to strengthen their case. Faith and politics worked together, not in opposition.

This fusion reflects broader medieval religious life in Scotland, later shaped through texts like those explored in Scottish Gaelic Bible Translations.

The document did not reject religion. It used faith to argue for justice and freedom.

The Role of Robert the Bruce

Robert the Bruce did not author the Declaration, but it defended his rule. The text makes one point very clear. Loyalty to the king depended on his defense of Scotland’s independence.

This conditional loyalty contrasts with absolute monarchy. It suggests accountability, a rare stance in medieval Europe.

The Declaration’s Lasting Legacy

The Pope eventually lifted Robert the Bruce’s excommunication. Scotland’s position strengthened over time. Yet the Declaration’s real power lies in its ideas.

Scholars often note parallels between the Declaration and later documents, including the American Declaration of Independence. While not a direct source, the philosophical overlap is undeniable.

The Declaration also reinforces Scotland’s cultural resilience, visible in traditions that survive today, from tartan symbolism (What Is Tartan?) to regional identity.

Why the Declaration of Arbroath Still Matters Today

The Declaration of Arbroath reminds us that freedom depends on collective responsibility. It insists that nations exist through shared commitment, not imposed rule.

In a modern world still negotiating sovereignty and identity, its message remains urgent. Scotland’s medieval voice still speaks, clear and confident, across seven centuries.