Iron Age Celtic Artifacts: Art, Power, and Belief

Iron Age Celtic artifacts provide one of the most vivid insights into ancient European societies. Dating roughly from 800 BCE to the Roman period, these objects reflect a culture where art, belief, and identity merged seamlessly. Celtic craftspeople did not create objects merely for utility. They embedded meaning into every curve, spiral, and symbol.

As someone trained in Celtic material culture, I often stress one point: Iron Age Celtic art speaks through form rather than text. Since the Celts left few written records, artifacts carry their stories. Each object reveals how people understood power, spirituality, and their place in the natural world.

The Visual Language of Iron Age Celtic Art

Celtic artists developed a distinctive visual language during the Iron Age. They favored flowing lines, spirals, trumpet shapes, and abstract animal forms. Symmetry mattered less than movement. The designs appear alive, constantly shifting.

This artistic approach reflected Celtic beliefs about cycles, transformation, and continuity. Nature influenced every motif. You can still trace this visual logic in later sacred traditions discussed in Celtic stone carvings.

Torcs: Symbols of Authority and Status

Among all Iron Age Celtic artifacts, the torc stands out most clearly. These rigid neck rings, often made of gold or bronze, symbolized power and elite status. Warriors and leaders wore them to display authority and divine favor.

Classical writers described Celtic warriors entering battle adorned with torcs. Archaeology confirms this link between adornment and identity. Many torcs appear in ritual hoards rather than graves, which suggests deliberate offerings rather than accidental loss.

The political and ritual importance of such offerings connects closely with sacred leadership centers like the Hill of Tara.

Weapons as Artistic Statements

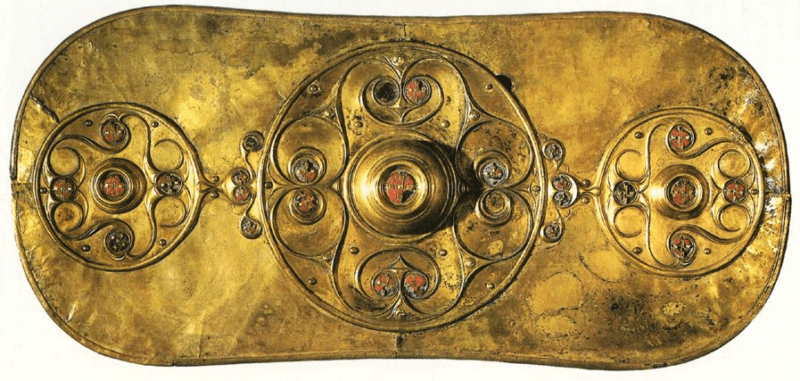

Iron Age Celtic weapons challenge modern ideas about warfare. Swords, shields, and helmets often carried elaborate decoration. Craftspeople engraved flowing patterns onto objects meant for combat.

The Battersea Shield remains one of the finest examples. Its thin bronze construction suggests ceremonial use, yet its decoration speaks of prestige and skill. Celtic warriors treated weapons as extensions of identity, not disposable tools.

This fusion of art and martial culture appears in myths surrounding skilled warrior-gods such as Lugh, who embodied both craftsmanship and battle prowess.

Everyday Objects with Deeper Meaning

Not all Iron Age Celtic artifacts belonged to elites. Archaeologists uncover brooches, mirrors, pottery, and tools across settlements. Even simple objects display careful design choices.

A brooch might signal family identity. A mirror could hold ritual significance rather than vanity. Celtic society did not draw sharp boundaries between sacred and ordinary life. Meaning infused daily existence.

This storytelling through objects echoes later oral traditions explored in why Irish people are natural storytellers.

Ritual Deposits and Sacred Landscapes

Many Iron Age Celtic artifacts come from rivers, bogs, and wetlands. These locations carried spiritual weight. Celts viewed water as a boundary between worlds.

Depositing valuable items into rivers formed part of religious practice. These acts honored gods, ancestors, or the land itself. Such beliefs survived well into the medieval period, shaping traditions discussed in Irish holy wells.

Why Iron Age Celtic Artifacts Still Matter

Iron Age Celtic artifacts continue to influence how we understand Celtic heritage today. Their designs inspire modern jewelry, visual art, and cultural identity. More importantly, they remind us that ancient societies communicated through material culture with remarkable sophistication.

To explore how visual identity evolved later, readers may find what is tartan a useful continuation of this story.

These artifacts do not simply belong to the past. They remain active voices in how Celtic history is remembered, studied, and celebrated.