The Celtic Ogham Alphabet: Ireland’s Oldest Script

The Celtic Ogham alphabet represents one of the earliest written systems used in Ireland and parts of western Britain. More than a script, Ogham acts as a cultural bridge between spoken tradition and recorded memory. Its linear marks carved into stone and wood reflect a society deeply rooted in landscape, language, and oral knowledge.

Irish culture long favored storytelling and spoken wisdom, a theme explored in depth in our discussion of why Irish people are natural storytellers. Ogham did not replace that oral world. It complemented it.

What Is the Ogham Alphabet?

Ogham (often spelled Ogma or Ogam) consists of twenty primary characters, known as feda. Each character appears as straight lines cut across or alongside a central stem line. The alphabet reads vertically from bottom to top.

Early inscriptions date from roughly the 4th to 6th centuries CE. Most appear on standing stones, often marking land boundaries, burial sites, or kinship claims. These stones still stand across Ireland, Wales, and parts of Scotland.

The structure of Ogham shows remarkable efficiency. Simple lines form a complete linguistic system, designed for carving rather than ink.

Mythic and Linguistic Origins

Tradition credits the invention of Ogham to Ogma, a god associated with eloquence and knowledge. This mythic origin reflects how language carried sacred weight in Celtic societies. Writing did not exist separately from belief.

Trees also shape the system. Many Ogham letters correspond to specific trees, linking language to the natural world. This symbolic connection mirrors themes found in Celtic sacred landscapes, including the enduring symbolism of the Celtic oak tree.

Ogham therefore operates on several levels at once: linguistic, symbolic, and spiritual.

Ogham Stones and the Landscape

Inscriptions of Ogham appear most frequently on stone monuments. These stones anchor identity to place. Names carved in stone declared ownership, ancestry, and legitimacy.

Such carvings share cultural ground with Ireland’s broader tradition of stone symbolism, explored further in our guide to Celtic stone carvings. Both traditions reflect a worldview where memory lived in material form.

Many stones stand near ancient ceremonial sites. Some lie close to the Hill of Tara, a landscape long associated with kingship and sovereignty. In this way, Ogham connects writing to power, territory, and lineage.

Ogham and the Irish Language

Ogham preserves some of the earliest known forms of the Irish language. These inscriptions provide invaluable evidence for linguists studying early Gaelic phonetics and structure.

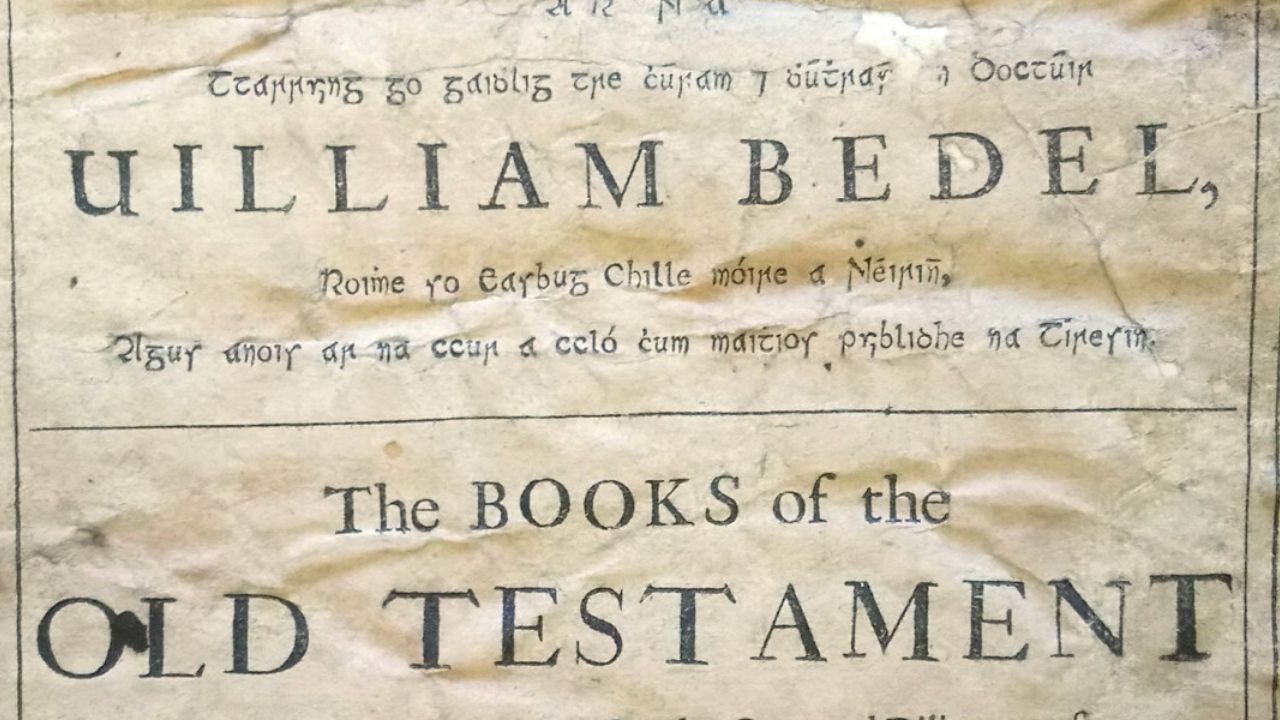

As Irish literacy evolved, Latin script gradually replaced Ogham. Still, Ogham never disappeared from cultural memory. Its influence echoes in later manuscript traditions and even in the reverence shown toward sacred texts, such as those explored in Scottish Gaelic Bible translations.

Ogham demonstrates how language adapts while retaining deep continuity.

Was Ogham Only Practical?

While many inscriptions appear functional, evidence suggests ritual use as well. Some later medieval sources describe Ogham as a learned system used by poets and scholars. Variants expanded beyond the original alphabet, sometimes for cryptic or symbolic purposes.

This scholarly role aligns with the broader Celtic respect for learned tradition, seen in poetic forms, proverbs, and structured knowledge systems. Ogham served as both record and riddle.

Why the Celtic Ogham Alphabet Still Matters

The Celtic Ogham alphabet matters because it captures a turning point. Speech began to meet stone. Memory began to fix itself in landscape. Yet creativity remained central.

Today, Ogham inspires modern art, tattoos, jewelry, and academic study. It appears in discussions of language revival and cultural identity. Its endurance proves that simplicity, when guided by meaning, can outlast centuries.

Ogham reminds us that writing once grew directly from the land it described.